-

History of:

- Resources about:

- More:

- Baby walkers

- Bakehouses

- Bed warmers

- Beer, ale mullers

- Besoms, broom-making

- Box, cabinet, and press beds

- Butter crocks, coolers

- Candle snuffers, tallow

- Clothes horses, airers

- Cooking on a peat fire

- Drying grounds

- Enamel cookware

- Fireplaces

- Irons for frills & ruffles

- Knitting sheaths, belts

- Laundry starch

- Log cabin beds

- Lye and chamber-lye

- Mangles

- Marseilles quilts

- Medieval beds

- Rag rugs

- Rushlights, dips & nips

- Straw mattresses

- Sugar cutters - nips & tongs

- Tablecloths

- Tinderboxes

- Washing bats and beetles

- Washing dollies

- List of all articles

Subscribe to RSS feed or get email updates.

When I again unclosed my eyes, a loud bell was ringing; the girls were up and dressing; day had not yet begun to dawn, and a rushlight or two burned in the room. I too rose reluctantly; it was bitter cold...

Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre, 1846

...a rush candle, from the wicker-hole of some clay habitation...

John Milton, Comus, 1634

Some address is required in dipping these rushes in the scalding fat or grease; but this knack also is to be attained by practice. The careful wife of an industrious Hampshire labourer obtains all her fat for nothing; for she saves the scummings of her bacon-pot for this use; and, if the grease abounds with salt, she causes the salt to precipitate to the bottom, by setting the scummings in a warm oven. Where hogs are not much in use, and especially by the sea- side, the coarser animal oils will come very cheap. A pound of common grease may be procured for four pence; and about six pounds of grease will dip a pound of rushes; and one pound of rushes may be bought for one shilling: so that a pound of rushes, medicated [impregnated with fat] and ready for use, will cost three shillings. If men that keep bees will mix a little wax with the grease, it will give it a consistency, and render it more cleanly, and make the rushes burn longer: mutton-suet [tallow] would have the same effect.

Gilbert White, Natural History of Selborne, c1789

Rushlights

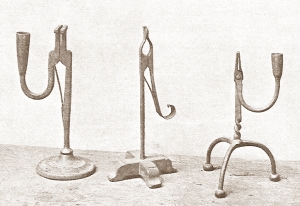

Rush dips, rushlight and splint holders, nips

Candlelight is beautiful, but

not cheap enough for everyone. For centuries beeswax candles were the best, lighting

up castles and cathedrals. Most people used

tallow (made from animal fat). The distinction between expensive wax and butcher's

tallow was underlined in one grand English household,

Wimpole Hall, by having the butler take charge of beeswax candles, while the housekeeper

kept account of the ordinary tallow candles. (Late 18th century)

Candlelight is beautiful, but

not cheap enough for everyone. For centuries beeswax candles were the best, lighting

up castles and cathedrals. Most people used

tallow (made from animal fat). The distinction between expensive wax and butcher's

tallow was underlined in one grand English household,

Wimpole Hall, by having the butler take charge of beeswax candles, while the housekeeper

kept account of the ordinary tallow candles. (Late 18th century)

In

small cottages there were people who could not afford any kind of candle. For them

a cheap alternative was a rushlight made from a rush dipped in grease, or a burning

splinter of wood. These were held pinched in a nip like pliers or tongs on a stand. (See photograph of a modern re-creation

left. Older rushlights might be thinner.) Nips were also called nippers or a pair

of nips. They could be combined with a candle-holder

for people who used both kinds of light, depending on their needs and budget at

different times.

In

small cottages there were people who could not afford any kind of candle. For them

a cheap alternative was a rushlight made from a rush dipped in grease, or a burning

splinter of wood. These were held pinched in a nip like pliers or tongs on a stand. (See photograph of a modern re-creation

left. Older rushlights might be thinner.) Nips were also called nippers or a pair

of nips. They could be combined with a candle-holder

for people who used both kinds of light, depending on their needs and budget at

different times.

Writers make it clear that rush lighting was a sign of poverty, or at least a humble lifestyle. In the 17th century Milton placed a "rush candle" in a lowly home made of clay and wicker. Two hundred years later Charlotte Brontë mentioned the rushlights as part of the overall deprivation Jane Eyre suffered at her miserable school. (See left-hand column) One 18th century novelist compared someone to:

...a rush-light, a little twinkling uncomfortable spark, which one is every moment afraid will vanish in smoke, and which the least wind will extinguish.

Anon, Anna Melvil, 1792

Even in the 19th century there were still people in Britain who depended on rushes

for light, and were unable to afford the price of candles. In a few areas burning

resinous softwood splinters was a possible alternative. The choice varied by region.

Where rushes grew well and a cool climate kept the fat set hard, as in much of the

UK,

rushlights were common. Other parts of Europe favoured pine splinters

or chips from other suitable woods. These could be gripped in wall-hung

splint-holders, standing

holders, or put on a plate-like

stand. Both rush- and splint-holders were used in North America.

Even in the 19th century there were still people in Britain who depended on rushes

for light, and were unable to afford the price of candles. In a few areas burning

resinous softwood splinters was a possible alternative. The choice varied by region.

Where rushes grew well and a cool climate kept the fat set hard, as in much of the

UK,

rushlights were common. Other parts of Europe favoured pine splinters

or chips from other suitable woods. These could be gripped in wall-hung

splint-holders, standing

holders, or put on a plate-like

stand. Both rush- and splint-holders were used in North America.

Rushlights were on sale cheaply in towns, but many country people made their own from juncus effusus, the soft rush. (Also used for chair seats, floor coverings, and much more.) In the late 18th century, the English naturalist Gilbert White calculated that even if you bought your rushlights ready-made, you need spend only one farthing (a quarter of a penny) for five and a half hours of light from a dipped rush. One single rushlight didn't give a lot of light, of course.

Making rushlights

A rushlight, also known as a rush dip

or candle, was made by dipping the pithy centre of a rush into kitchen grease. In

summer children and adults picked rushes, the bigger the better, and put them to

soak in water until they could be peeled. Skilful peeling left one narrow strip

of the outer covering to help the rushes keep their shape. After the peeled rushes

were dried, they were dipped in leftover kitchen fat. This had been collected over

time in iron grease pans, which were then warmed at the fireside to re-liquify the

grease.

A rushlight, also known as a rush dip

or candle, was made by dipping the pithy centre of a rush into kitchen grease. In

summer children and adults picked rushes, the bigger the better, and put them to

soak in water until they could be peeled. Skilful peeling left one narrow strip

of the outer covering to help the rushes keep their shape. After the peeled rushes

were dried, they were dipped in leftover kitchen fat. This had been collected over

time in iron grease pans, which were then warmed at the fireside to re-liquify the

grease.

Gertrude Jekyll photographed the equipment needed for making and using rushlights in Surrey, southern England, around 1900. Her information came from a 90-year-old "cottage friend" who peeled rushes for her, and explained how to dip bunches of a dozen or so at a time, "keeping 'em well under". She recommended mutton fat when possible, as that set harder than other grease, and said her mother had always laid the dipped rushes on a piece of bark to dry. (Below right)

Jekyll says that the

oldest rushlight holders in her part of the world all had upright nips. Horizontal

nips and candle-sockets were signs of a newer holder. Moving the rushlight along

from time to time was a job for children:

Jekyll says that the

oldest rushlight holders in her part of the world all had upright nips. Horizontal

nips and candle-sockets were signs of a newer holder. Moving the rushlight along

from time to time was a job for children:

About an inch and a half was pulled up above the jaw of the holder. A rush-light fifteen inches long would burn about half-an-hour. The frequent shifting was the work of a child. It was a greasy job, not suited to the fingers of the mother at her needle-work. 'Mend the light' or 'mend the rush' was the signal for the child to put up a new length.

Gertrude Jekyll, Old West Surrey, 1904

Apart from the weak light and

the smell of burning kitchen fat, there were other drawbacks. You needed a rag to

catch dripping grease, and bedside furniture was often scorched by a rushlight that

had been placed flat, overhanging the edge, but not extinguished in time. A neat

way of snuffing a rushlight was by using "two pins crossed".

Apart from the weak light and

the smell of burning kitchen fat, there were other drawbacks. You needed a rag to

catch dripping grease, and bedside furniture was often scorched by a rushlight that

had been placed flat, overhanging the edge, but not extinguished in time. A neat

way of snuffing a rushlight was by using "two pins crossed".

As well as using holders a few inches high, some homes had free-standing iron or wooden holders, with a mechanism for adjusting the position of the nips and varying the height of the rushlight. (Above left)

2 January 2008

2 January 2008

You may like our new sister site Home Things Past where you'll find articles about antiques, vintage kitchen stuff, crafts, and other things to do with home life in the past. There's space for comments and discussion too. Please do take a look and add your thoughts. (Comments don't appear instantly.)

For sources please refer to the books page, and/or the excerpts quoted on the pages of this website, and note that many links lead to museum sites. Feel free to ask if you're looking for a specific reference - feedback is always welcome anyway. Unfortunately, it's not possible to help you with queries about prices or valuation.